The International Thermonuclear

Experimental Reactor

A Huge Investment

The international thermonuclear experimental reactor (ITER) most closely follows the design of proposals I was aware of when I first heard of and became interested in nuclear fusion as a teenager. It has a number of issues of concern but is the most widely funded option out there.

Magnetically confining a superhot plasma of hydrogen isotopes in a huge tokamak in Cadarache in the south of France, this project is the first stage in a number of steps to build a nuclear fusion power station.

All photographs and diagrams courtesy of ITER

Andrei Sakharov, the noted USSR nuclear scientist and dissident, first proposed the tokamak idea in 1950. Initially it became the standard design in Russia and later in the West as it demonstrated its superior ability to powerfully contain high temperature plasmas.

From 1985 initial discussions towards the international thermonuclear experimental reactor began between Euratom in the European Union, the USSR, Japan and the USA.

Actual construction was agreed to in 2006. At this point China, India and South Korea had joined in support for the project, with a brief withdrawal by the USA before this.

Each nation was contracted to contribute 9% of the costs, with the European Union responsible for 46% as it would host the facility.

There had been vigorous discussions as to who would have first pickings.

Japan's Involvement

A disappointed Japan has agreements for further development constructions later. The IFMIF - International Fusion Irradiation Materials Facility - for testing suitability of materials for ITER is located in Japan.

It also supplies the current director of the international thermonuclear experimental reactor in Osamu Motojima. He had to release news of unwanted delays since the March 2011 earthquake and tsunami in his home country.

Problems had been demonstrated in Swiss tests of a sample superconducting cable to be manufactured in Japan.

The Japanese facilities of the Naka Fusion Institute of the Japan Atomic Energy Agency were to have been testing for faults in the cable. They were also supposed to be testing and developing magnets and heating components. Damage to the building has prevented access.

Delays And Costs

By arranging alternatives a maximum delay of a year is hoped for. The Japanese coil manufacturing plants were apparently not damaged.

Already there had been other delays and cost over-runs. Proposed initial testing dates had been delayed already by three years to 2019.

Also the expected cost had ballooned from 5 to 15 billion Euro.

The European Union countries have yet to find the 1.3 billion Euro to fund their 2012 and 2013 contribution - but feel it will be found. They are concerned the funding will not detract from funding for other alternative energy initiatives.

At least this was better than the USA 2011 contribution of $80 million which was released in April a year later only after discretionary spending discussions in Congress.

Design Details Of The International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor

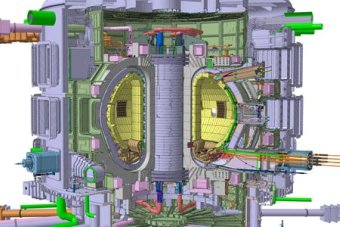

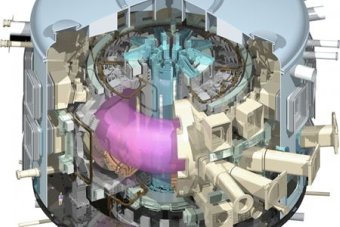

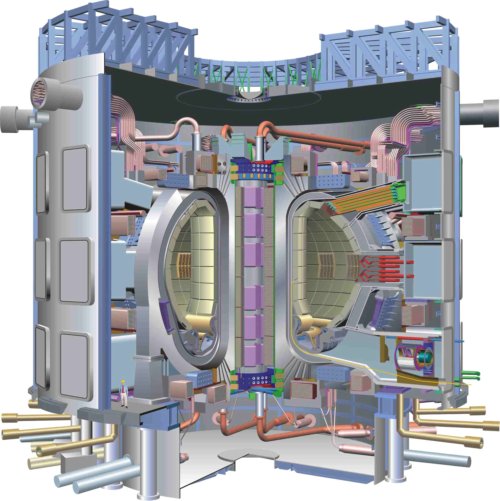

The design calls for a huge vacuum chamber to house the superheated plasma with 18 vertical toroidal "D"-shaped magnets and six horizontal poloidal field magnets. Five of the six poloidal coils are to be constructed on site in the building currently underway on the the site.

Current is supplied through the plasma. But the poloidal field magnets cause modification of the edges of the fields to maintain a stable state. At the edges of plasma fields eddies and bubbles occur which can lead to loss of form and energy.

At the centre of this doughnut arrangement is the vertical solenoid coil with six independent coil packs. This area induces the current in the plasma and maintains vertical stability control.

The central solenoid coils use a niobium-tin alloy carrying 46 kiloAmps of current, generating 13.5 teslas of magnetic field.

The 18 toroidal coils are made from the same alloy and aim to generate 11.8 teslas of magnetic field.

Poloidal and correction coils are made from a niobium-titanium alloy.

To enable superconduction the coils are cooled to 4 degrees Kelvin.

The chamber will be evacuated. The vacuum for this is currently being tested in Belgium.

Inside the reactor will be half a gram at a time only of the deuterium and tritium hydrogen isotope fuel - enough for an hour of running - unlike years of fuel in nuclear fission reactors.

The goal of the international thermonuclear experimental reactor is to produce 500 MegaWatts of power from an input power of 50 MegaWatts.

A surrounding blanket of molten lithium will absorb generated neutrons creating more tritium fuel in the process.

Beyond The Experiment

The heat from this reaction will be removed. But in the next stage of the project, the DEMO construction, initially slated to be up and running in the late 2030s and feeding power into the grid by 2040, will aim to use this energy to heat water or another similar coolant to drive drive turbines to produce electrical power.

General release of the technology for world-wide use was expected in the last quarter of the twenty-first century. Current delays will extend this roll-out time.

Preparations

The initial Cadarache site a kilometre long and 400 metres wide was levelled by May 2009.

A 17 metre deep excavation pit to hold the tokamak construction and acting as an earthquake isolation pad had been completed in June 2011. Concrete has been poured into water-scoured crevices in the platform floor.

The poloidal field coil winding building to house the on-site coil winding for the five poloidal coils was getting insulation and roof cladding in June 2011.

The name international thermonuclear experimental reactor has been modified at times to international tokamak experimental reactor and, more commonly, simply ITER (eat-er) due to negative connotations for the words thermonuclear and experimental.

Cooperation with the Culham, UK, JET (Joint European Torus) program has been arranged to test various elements of design.

The international thermonuclear experimental reactor itself will still be many years in development. It will be 2020+ before some useful results are available.

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.